We commissioned Juwairiyyah Wali to review our Film Feels Curious launch event at Flatpack Film Festival 2022.

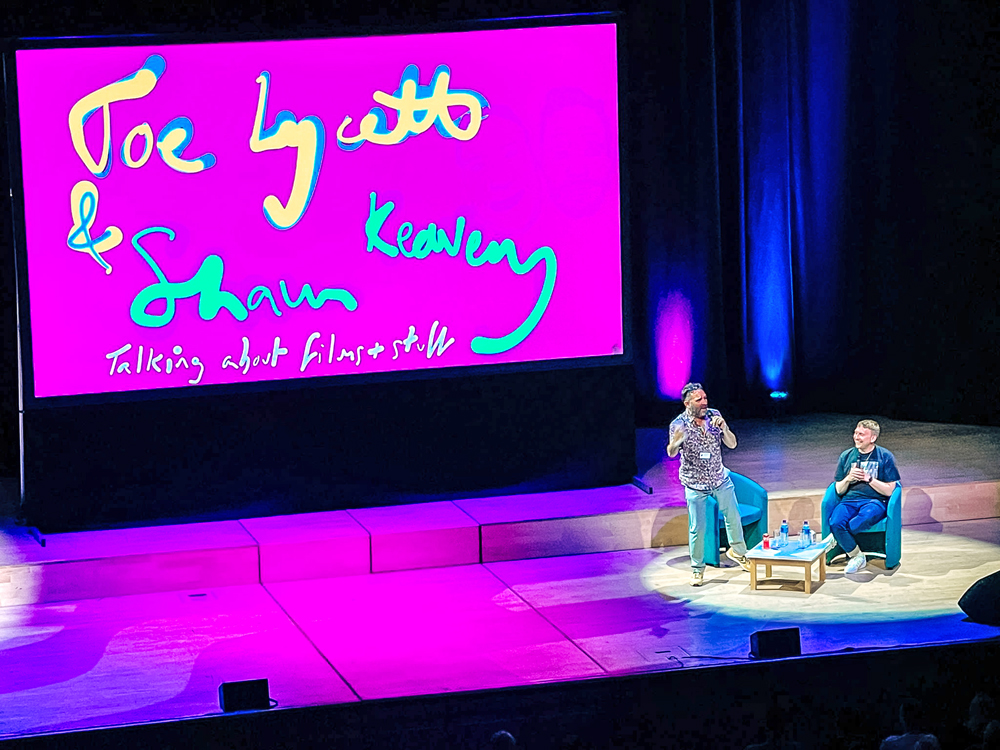

What does a curious approach to filmmaking look like? This is something that UK-wide independent cinemas and festivals have to explore as part of the Film Feels Curious season, encouraging them to uncover distinctive styles, investigative themes, unique filmmakers and more. As a response to this, Flatpack Festival kicked off their 2022 programme with Brummie comedian Joe Lycett and radio host Shaun Keaveny at the Birmingham Town Hall, delving into Joe’s recent curious pursuits of filmmaking.

As an audience member at the Flatpack Presents: Joe Lycett's Curiosities with Shaun Keaveny event, I myself embodied many of the attributes that stem from the word ‘curious’. With little prior knowledge of Joe Lycett’s filmmaking ventures, I was interested to discover the multitude of Joe’s creative outputs. Most commonly labelled as a comedian, Joe avoids being pigeonholed in the entertainment industry by establishing himself as a filmmaker, artist, and TV personality, skilfully applying his knack for comedy through various different creative avenues.

The versatility of Joe’s approach to arts and entertainment ran through the event, which was hosted by himself and radio DJ Shaun Keaveny. Unpacking Joe’s lifetime of inspirations, the pair covered everything from cheesy 80s public service announcements to big budget commercial advertisements, all screened alongside Joe’s own music videos and shorts - including the world premiere of Joe’s film Ray (2022). As Shaun picked Joe’s brain, a common theme that seemed to connect Joe's ideas and filmmaking was working with limitations; working within the limits of what’s possible and with external restrictions that were both in and out of his control. Being met with barriers to production and having to work within certain parameters is an obstacle many filmmakers will be able to relate to, and finding ways to put together creative outputs on a budget is challenging work. The impact of COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns occurring globally was a common denominator in the challenges filmmakers were facing, sometimes regardless of budget.

Filmmakers, both emerging and established, were faced with an excess of time, and yet due to the need for social distancing, they were still confined to the restricted space of their homes. Like many films created during lockdown, Joe Lycett’s comedic short Little Sammy Sloth (2021) seemed to be born out of boredom, creativity and a curiosity around what could be achieved with the bare minimum. Little Sammy Sloth embodies the space filmmakers had during lockdown to make for the sake of making, filmmaking that’s detached from the scrutiny of audience reception, and the pressures of revenue. Creating space instead for playfulness, authenticity and stretching the boundaries of what’s possible with film during a global pandemic. As a result, the film accurately captures what Joe refers to as a ‘simple idea’. Stripped from big budget set designs, Joe’s melancholic tale of a stuffed sloth who just wants some attention is quite obviously a lockdown project, but stands out in its bizarreness through the unexpectedly crass but comedic climax; ultimately pointing to the idea that film doesn’t necessarily need to be undercut by complex storylines, extensive set design, or the most fluid of dialogues to make an impact or be enjoyable to watch.

Beyond the lockdown home filmmaking phenomenon, Joe showcases some of his most memorable sources of inspiration, and once again delves into unexpected territory as he unpacks his love for advertisements, making references to big brands like Honda, Cadbury, and Kenzo - describing this particular stream of media as ‘the golden era of advertisements’. Expertly avoiding critically acclaimed, award winning filmmaking and going for what could be considered the ‘low brow’ commercials that you might be watching in between weeknight episodes of Love Island, feels slightly ‘anti-establishment’. Not everyone will be watching the latest critically acclaimed arthouse release at their nearest independent cinema, or in fact have access to it, but there was a time where nearly 20 million viewers tuned into The X Factor final on the same night.

What Joe displays here is the idea of sourcing inspiration from anywhere at any time. You don’t have to be a cinephile to make films, and this leads to a sort of democratisation of film culture, escaping pretentiousness and paving the way for new and alternative ways to make film. Big budgets and unbridled creative freedom do not automatically equate to whatever the definition of a ‘good’ film might currently be defined as. Sometimes having restrictions in place can fuel your curiosities as a filmmaker and, searching for unconventional solutions around these limitations, can point towards the making of films similar to Joe Lycetts’s: playful, witty, and off the beaten track.