“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse…” Leonora Carrington

Leonora Carrington, El mundo magico de los Mayas, 1963-1964

Surrealism is a movement built on women’s bodies. Many well-known surrealist images – a woman’s bare back painted to resemble a violin, a sofa in the shape of a pair of lips – draw upon the female form, while anonymous nudes litter the work of Man Ray, Salvador Dali and Max Ernst. Yet although it has long been acknowledged that women were closely associated with the movement, for much of the past century their contribution has largely been discussed in passive terms. Male artists often drew upon their wives and lovers as assistants and muses, but they also generally refused to acknowledge the independent contributions of their female peers. The 1924 surrealist manifesto entirely excluded female artists, an omission that would continue to be replicated over the decades. It’s only thanks to the hard work of feminist critics, that the true contribution of artists such as Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning and Meret Oppenheim, have finally begun to be properly acknowledged.

Curators and researchers Rachel Ashenden and Molly Gilroy are very much part of this wave of rediscovery. In 2020, they published the first edition of The Debutante, a feminist surrealist journal which aims to increase the profile of women within the movement. Now, by co-curating the Electric Muses tour, Ashenden and Gilroy are expanding their mission to encompass the work of feminist surrealist filmmakers. “While many people might be able to name (male) surrealist directors like Luis Bunuel, David Lynch and Jan Švankmajer, women surrealist filmmakers are less in the public consciousness,” says Ashenden. “Maya Deren or Germaine Dulac may not necessarily be household names yet, but we’d sure like them to be.”

Electric Muses presents a compelling case for the enduring power of these filmmakers. A collaboration between The Debutant and Cinetopia, the programme consists of four films spanning the 1920s to the 1990s, alongside live scores from composers Aurora Engine and Bell Lungs. By combining these pioneering works with boundary pushing music from female musicians, Electric Muses highlights the technically innovative work of women across artforms, while also breathing new life into the film archive. “Women surrealists are not a thing of the past, nor a footnote in an art history book,” says Ashenden. “There are so many beautiful synergies between heyday surrealism and contemporary filmmaking practice. Ultimately, we want our audience to know that feminist surrealism is alive and thriving.”

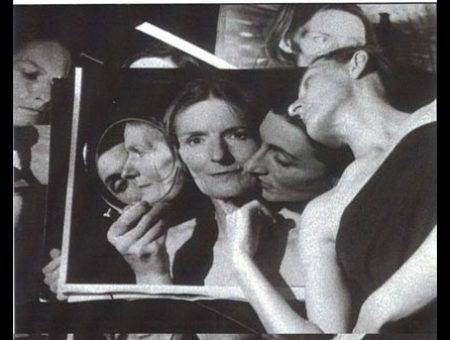

Still from The Seashell and the Clergyman (Germaine Dulac, 1928)

The centrepiece of Electric Muses is French filmmaker Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell and The Clergyman (1928). Considered to be the first work of surrealist cinema, Dulac’s film has long been overshadowed by Dali and Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), which premiered a year later and built on techniques pioneered by Dulac. While every student of experimental film will be familiar with the latter’s infamous scenes of eyeball slicing and ant-infested wounds, fewer are likely to have seen the equally potent images – a mirrored orb, a crawling man, a head split in two - that flood Dulac’s earlier film.

Dulac was already renowned as a director of documentaries and melodramas before she switched her attention to the avant-garde. In The Seashell, she establishes many of the hallmarks that would go on to define surrealist filmmaking. The film places us directly inside the subconscious of a young clergyman as he pursues an obsessive lust for a beautiful aristocrat. His attempts to seduce this woman are continuously thwarted by the appearance of a forbidding older man, alternately dressed as a bishop and an army general. Within the nightmarish logic of the film, this man comes to represent a kind of unassailable masculinity in contrast to the increasingly impotent clergyman.

Surrealism is a movement obsessed with time - the most iconic surrealist image after all, is that of Dali’s melting clocks - so it’s unsurprising that by turning to a time-based medium Dulac was able to unlock new creative possibilities. She rejects conventional narrative, instead using the form to reflect the leaps and lapses that characterise the subconscious mind. Techniques such as super imposition, cross dissolves and montage, allow Dulac to establish a distinctive aesthetic language for this new genre. Her mischievous undermining of masculine religious authority also positions surrealist film as a genre built on rebellion and iconoclasm.

Still from Meshes of the Afternoon (Germaine Dulac, 1943)

The foundations laid by Dulac in The Seashell would subsequently be expanded upon by generations of exceptional female filmmakers, the most famous of which is undoubtedly Maya Deren. Like Dulac, Deren was a formidable multi-hyphenate – a dancer, choreographer, philosopher and writer – who drew upon a range of influences spanning African ritual to Freudian theory, to hone a singular style.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is Deren’s first and best known film. Co-directed with husband Alexander Hammid, Meshes is a journey through the unconscious which follows a woman (Deren) as she enters her home, falls asleep and dreams of being followed by a mysterious veiled figure. It’s a beguiling mobius strip of a movie soaked in psychoanalytical symbols – a key, a knife, a loaf of bread – and built around disorientating camera angles and shots of Deren’s bisected body, a hand here, an eye there. It’s easy to see why Deren is often seen as a precursor to David Lynch; with its circular structure, dream logic and sun-soaked LA setting, Meshes shares much DNA with Mulholland Drive (2001).

Deren was also a formative influence on another American filmmaker. As a student in the early 1970s, Barbara Hammer encountered Deren’s films for the first time and was blown away. Hammer would go on to forge her own distinctive style and pioneer queer experimental filmmaking, but in her early work we can clearly detect Deren’s legacy in Hammer’s use of her own body and her fascination with psychoanalysis.

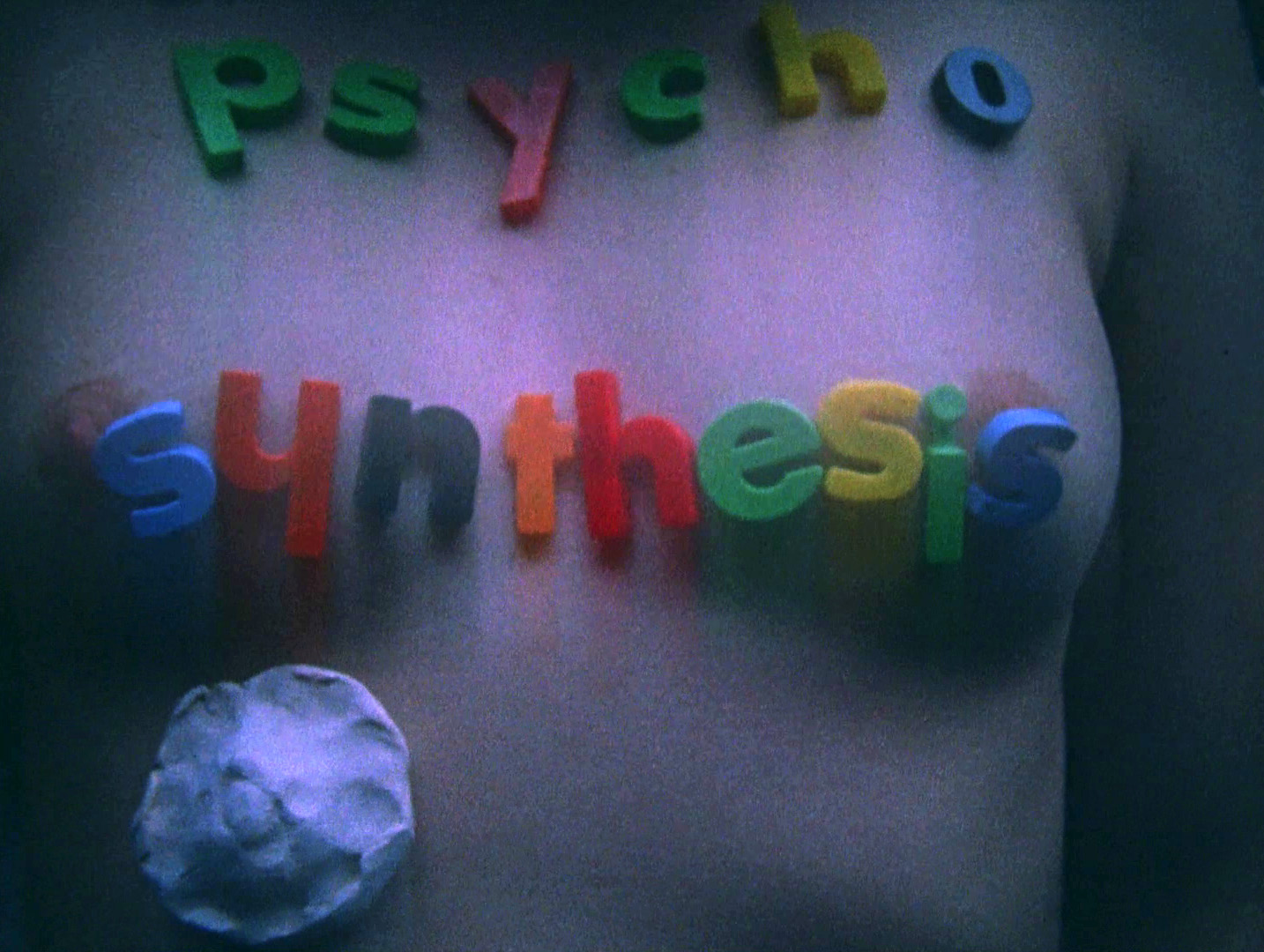

Still from Psychosynthesis (Barbara Hammer, 1975)

Hammer’s Psychosynthesis (1975) is a kind of psychoanalytical autobiography; as the filmmaker announces in the opening voiceover, this is “a gestalt fantasy work uniting my sub personalities of athlete, baby, witch and artist.” Six delightfully unhinged minutes follow, as we are presented with a carousel of subversive images – a trampolining woman, a coven of witches, flashes of eyes and breasts – which are punctuated by a soundtrack of cackling, weeping and panting. Along the way there are self-reflexive glimpses of the artist herself, carrying her camera and examining negatives. By depicting her own naked body in her work, Hammer offers a sly riposte to the anonymous female nudes so beloved of male surrealists. Through Hammer’s lens, bare breasts and torsos become a marker of freedom rather than objectification.

As Hammer’s Psychosynthesis demonstrates, one of the key hallmarks of feminist surrealism is the disruption of images of conventional femininity. In You Be Mother (1990) British artist Sarah Pucill takes on similar ideas in order to transform a mundane ritual – the pouring of tea – into an unnerving exploration of the relationship of women to the home. The film consists of a series of drawn out images of teamaking rendered uncanny by unexpected camera angles, close ups and stop motion. Just as both Hammer and Deren insert themselves into their work, so the film gradually reveals itself as self-portrait, with images of the artist’s face appearing projected onto the crockery.

The eerie and atmospheric You Be Mother is clearly heavily indebted to surrealist artists across mediums. The appearance of a pair of lips in a teacup brings to mind Meret Oppenheim’s Object (Breakfast in Fur) (1936), a fur-covered cup, saucer and spoon which has become an iconic surrealist object, while Pucill’s projected face is styled to be reminiscent of the work of gender-fluid photographer Claude Cahun. By gesturing outwards towards these influences, Pucill places herself in relation to a rich history of feminist surrealist practice in all its forms.

Still from 'Stages of Mourning' (Sarah Pucill, 2004)

When viewed alongside Dulac, Deren and Hammer, we see how Pucill’s work serves as a continuation of a legacy spanning more than seventy years. While the heyday of the surrealist movement is widely considered to have ended in the mid-1960s, the language of the feminist surreal can be traced to this day, in the films of Lucille Hadzihalilovic, Julia Ducournau and Ildiko Enyedi. The work of these visionary female filmmakers stands as a testament to the lasting potency of this most strange and unusual of movements. Have no doubt, the feminist surreal is alive, thriving and as wonderfully weird as ever.

Rachel Pronger is a writer, curator and co-founder of feminist film collective Invisible Women.